On August 15th 1945, Imperial Japan surrendered to the Allies, effectively bringing the Second World War to a close. VJ Day is commemorated annually on this date in the UK, and on September 2nd in the US, the day the surrender document was finally signed. This year [2020], as you are doubtless aware, was the 75th anniversary and sadly the commemorations had to be reined in due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

VJ Day has always been something of a poor relation to VE Day, yet many Berkshire villages had men who were in the Far East, Purley included. Several villagers, including subsequent incomers, would later briefly recall their ordeal in the camps, including one of Purley’s rectors. Revd William Morton sustained a leg injury so severe, that he was never again able to kneel. Two Purley men died in the camps. What follows is my attempt in lock-down to recreate their stories.

John Dudley Matthews was Purley’s rector between 1902 and his death in December 1914. His time in Purley wasn’t without its dramas, not least his death whilst attempting to row back from Mapledurham, having taken evensong there. He made at least two highly controversial decisions, one of which resulted in questions being asked in the House of Commons. Several sons served in the military, two surviving the First World War. As did daughter Rose, who served as a VAD in Reading.

Ernest Dudley Matthews, John’s second son, served with the Royal Garrison Artillery and, by the mid-1920s, had risen to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. By 1924, he was in Hong Kong, and by 1929, sufficiently settled for wife, Clara, to join him. On retirement, they remained in Hong Kong, probate records listing their address as 4 Armand Buildings, Kowloon. Armand Buildings has long gone, but was probably on Kimberley Road, known for its high-rise apartments. Life was probably good, certainly for Ernest, who seemingly spent considerable time at the Royal Hong Kong Golf Club, of which he was secretary for almost twenty years, according to one newspaper report.

In July and August 1940 the British Government, unable to defend Hong Kong and convinced it would fall to the Japanese, began evacuating British citizens. The hurried and compulsory evacuations attracted considerable criticism. Not least of racism, as the local Chinese population were excluded, as were British passport holders with non-European ancestry. As a result, the remaining evacuations were made non-compulsory, “evacuees” could remain provided that they volunteered for auxiliary roles. The Matthews’, it would appear, opted to do just that, Ernest becoming an ARP warden.

The anticipated surrender to Japanese forces came on Christmas Day 1941, later known as Black Christmas. In early January 1942, foreign nationals, including the Matthews’, were rounded up and eventually imprisoned in the Stanley Internment Camp, hastily set up in the grounds of the prison and a school. Internees soon discovered there were few amenities. No cooking facilities, no furniture, little crockery, or cutlery. The toilet facilities were dirty, inadequate, and without water. Whilst conditions were basic, they were good compared to many other Japanese camps. However, both food and medical supplies were in extremely short supply, the prisoners being essentially locked up and left to fend for themselves.

Between 1942 and 1945, 121 prisoners died here. A few were executed, but most died of malnutrition or medical conditions, including Ernest in January 1944. He was aged 68. Clara survived to liberation and returned to the UK in October 1945, on one of the earliest possible ships.

Whilst the conditions in which Ernest and Clara Matthews were imprisoned were basic and unsanitary, those Edward John Reed had to endure were far worse.

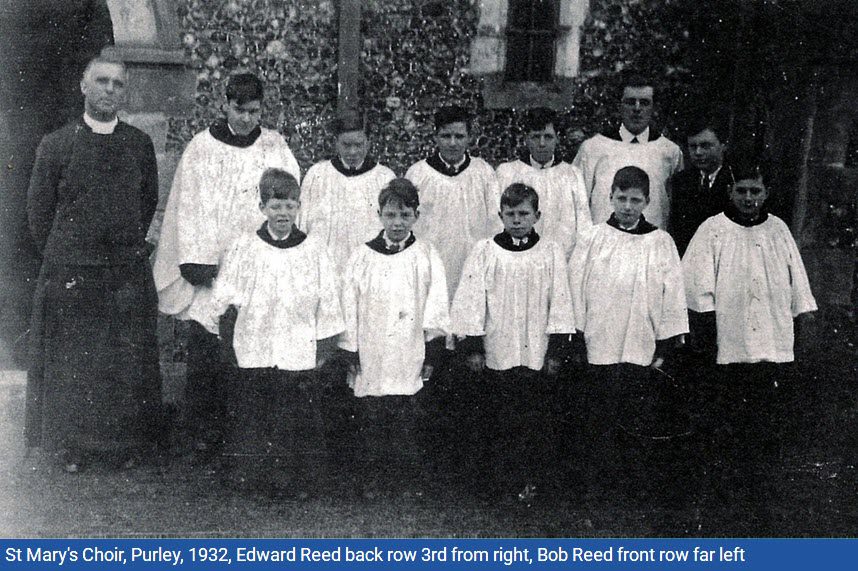

The Reeds were well established in the community of Purley. In a photograph of St Mary’s choir taken in 1932, 16-year-old “Ted” stares seriously at the camera from the back row. In the front, younger brother Bob grins broadly. The Reeds had moved into a new council house in Glebe Road, just three years earlier. George and Rose had at least seven children, Edward being third from youngest.

By that time, Edward’s father, George, was a brick layer. However, by profession he was a musician and had served at least two terms as a bandsman with the Royal Berkshire Regiment. He saw active service in the South Africa War and the First World War. Edward’s elder brother, Clement, also served with the Berkshire Regiment. So, the Reed family also had plenty of experience of military service.

Edward would also enlist, but with the Royal Engineers. At the outbreak of war, he was a Lance Corporal with the 35th Fortress Company, and a photograph taken in 1941 shows an older, strapping Edward with his Company rugby team in Malaya. By 1940, the 35th Fortress Company was one of a number of units protecting Singapore, believed by many to be impregnable. After a prolonged assault, Singapore fell to the Japanese in February 1942 and Edward was one of about 80,000 British, Indian, and Australian troops who became prisoners of war. They joined 50,000 taken prisoner by the Japanese in the earlier Malayan Campaign.

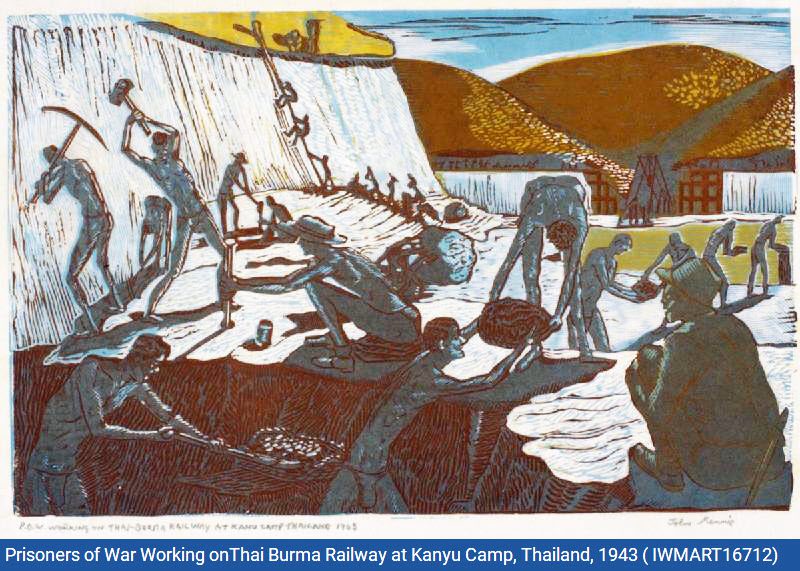

Edward would have soon found that life was harsh within the Japanese camps. Like thousands of others, he was forced to build the Thai-Burma railway, known as the ‘Death Railway’. Working conditions were barbaric and included long hours of intense heavy labour with minimal food and water. International Red Cross standards were not followed, and escape was nearly impossible. Dysentery, malaria, and tropical ulcers were rampant, contributing to the deaths of nearly one in four prisoners.

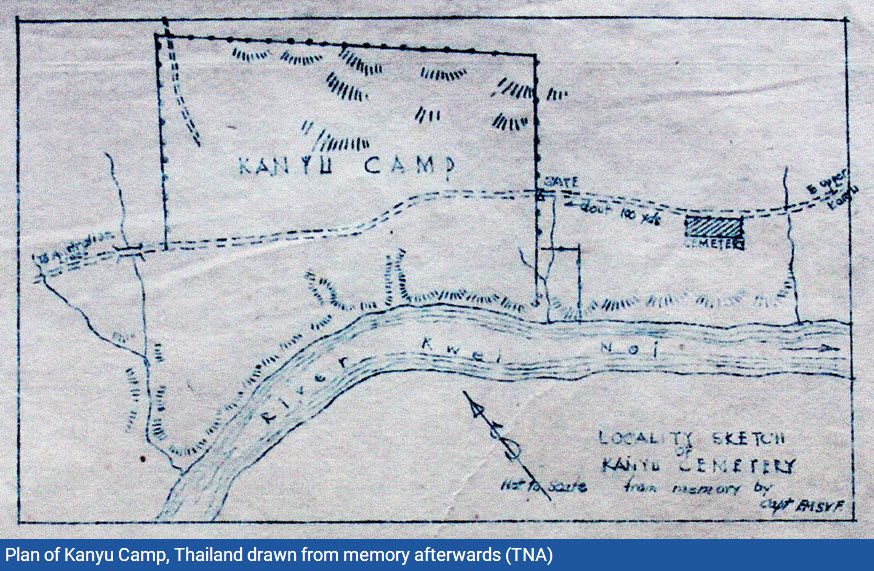

Sometime probably in late May 1943 Edward was moved to the Kanyu No.1 Camp , one of five in this locality. We can tell this by examining Commonwealth War Graves Commissions’ Graves Concentration Reports, and The National Archives’ WO 361/2235, both online. The latter lists the Thailand-Burma railway camps and contains death rolls, plans and maps drawn up by survivors. For anyone researching the railway camps, it is fascinating reading.

The camp bordered the River Kwai with its cemetery 100 yards outside its main gate. Deaths at this camp are all recorded between June 1st and July 30th 1943, suggesting it was only in use for a short period of time, presumably whilst the land was being cleared and track laid for that stretch of the railway. The Japanese prisoner of war index cards (Fol d3) confirm that Edward died there on the June 12th of indigestion, a common description in their records. However, the more detailed survivor accounts point to it being toxic peritonitis and dysentery. Dysentery was the biggest killer by far in No.1 Camp. Nearby, at Lower Kanyu Camp, it was cholera which filled their cemetery.

Edward was 27 years old when he died. He was buried in grave No.25 in the camp cemetery, his grave adjoining the main path which led to the camps gates. When the war ended, those buried in the camp cemeteries (Americans excepted, whose remains were repatriated) were transferred into three cemeteries at Chungkai and Kanchanaburi in Thailand and Thanbyuzayat in Myanmar. Along with all of those who died in the southern section of the railway, Edward was reburied in Kanchanaburi War Cemetery.

Edwards’s parents had been informed that he was missing and then received confirmation that he was alive and a prisoner of war. A nephew later recalled that “Gran ran up Glebe Road to show the neighbours”. Sadly, news of his death followed shortly afterwards. One can only imagine their continued suffering when details slowly emerged of the terrible suffering within the Japanese camps.