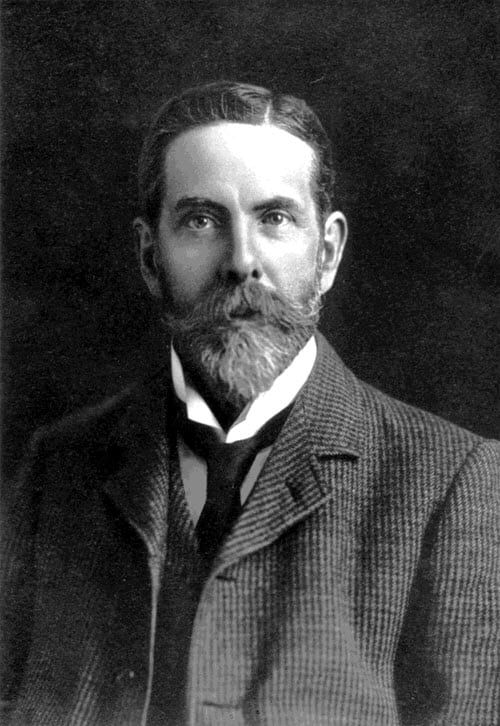

Henry Marriage Wallis – although a name likely to be unknown to many – had several prominent roles during his time in Reading.

Born in Ipswich, Suffolk in 1854, Henry Marriage was the son of Henry (senior), a corn merchant, and Elizabeth (nee Reckitt). Henry M had three sisters and the family lived comfortably around the Ipswich area.

His paternal grandmother’s maiden name was Marriage, hence his unusual middle name.

The family were Quakers and Henry continued his association with the Society of Friends throughout his life. He was educated at Bootham School, York from 1865-1869.

Henry’s father appears in Reading’s trade directories from 1874 as an ‘artificial manure and oilcake manufacturer and corn merchant’ at Reigate Wharf, Kings Road.

Within a couple of years he had succeeded the long established John May in the coal trade, at Victoria Wharf, 66 Kings Road, Reading, and was living in the recently built Dorset Villa in Craven Road.

He died in 1899 at his home, The Lawn, Upper Redlands Road.

The business continued until 1939 in the guise of Wallis, Son and Wells, with Henry’s involvement ending in 1909.

Henry married Sarah Crosfield, the daughter of a tea merchant, in 1878.

The marriage information has Henry’s residence as Sunderland in Durham. The Berkshire Chronicle of 31st August 1878 states:

‘Aug 22, at the Friends Meeting House, Reigate, Henry M Wallis, son of Henry Wallis, of Reading, to Sarah Elizabeth, second daughter of Joseph Crosfield, of the Dingle, Reigate.’

In 1881, Henry, Sarah and their son, Anthony (b.1879) appear in the census at Southern Hill, Reading. Later that year the family welcomed their second son, Basil.

The family continued to live in the Upper Redlands Road/Southern Hill area of Reading until 1899, when they appear at Ashton Lodge (No. 40) Christchurch Road. Sarah died in January 1886, leaving Henry a widower with two young sons.

In need of support in raising his sons, Henry moved back in with his father and sister. In 1891 he remarried to Annie Laird Hurry and had three further children (Rosamond b. 1892, Elliott b. 1897 and Violet b. 1898).

Soon after his arrival in Reading, Henry threw himself into local politics and law by becoming a prominent figure in the Reading Liberal scene, becoming Vice-President of the Reading Young Liberal Association.

By the mid 1890’s, he was involved in several local organisations – Reading branch of NSPCC, Reading Literary and Scientific Society, Reading Fat Stock Association. By 1881, he had founded the Reading Natural History Society.

On 21st December 1894 Henry was sworn in as a magistrate on the Reading Borough Bench following the receipt by the Town Clerk (Mr Henry Day) from the Home Office of the names of the gentlemen appointed to that role.

This list returned to the Town Clerk was much shorter than the one sent by the Council to the Lord Chancellor. The Berkshire Chronicle labelled it:

‘…the second instance of Radical jobbery in appointing magistrates for the borough since the Government were returned to power in 1892.’

Henry continued in his role as Justice of the Peace for Reading Borough Bench until 1924, over thirty years service to the town of Reading.

By 1911, Henry was again a widower, with his youngest child being 13 years of age. It’s at this point in his life when his humanitarian efforts come to the fore and make it in to the newspapers.

In 1912, the Dorking and Leatherhead Advertiser, Epsom District Times and County Post of Saturday November 16 states that Henry offered to go out to Bulgaria at his own expenses, to oversee the distribution of funds (from the Society of Friends Relief Fund).

His offer was accepted and he stated he intended to proceed immediately to Sofia to superintend the work of relief.

In Jan 1914, as the administrator of funds of over £15,000 for the relief of non-combatant sufferers in the late Balkan War, he received a letter of thanks from the Queen of Bulgaria.

Later that year, Henry was involved in the control and housing of Belgian refugees in Reading.

From September 1914 to October 1915, over 200 refugees were received in Reading, eight of whom had a cottage in Bucklebury put at their disposal by Henry.

Henry was a prolific writer of papers and essays on a vast array of topics from literary to architecture to scientific to natural history.

He wrote a piece on Archbishop Laud for ‘Some Worthies of Reading’ by John James Cooper (1923, The Swarthmore Press Ltd.), and also wrote novels under the nom de plume Ashton Hilliers (names used in two of his homes in Reading).

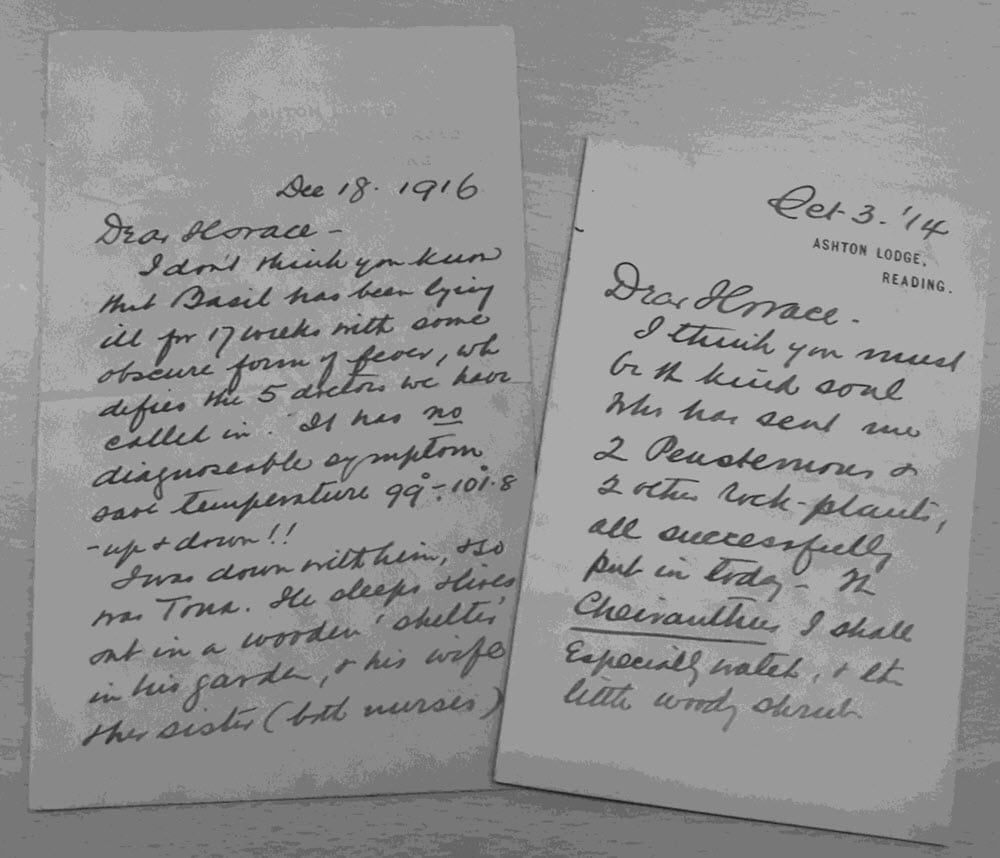

In addition, he wrote many letters, two of which came to us from the archives of the University of Lisburn in Northern Ireland. These two letters date from 1914 and 1916 and give an insight into Henry’s character.

In the letter dated ‘Oct 3 ’14’, Henry writes:

‘We are full up with Belgians – 148 are ‘bedded out’ (literally) in Reading & neighbourhood.

We know so many, & believe around 20 more are among us. Some are sick, & low & very miserable – others not so bad.

But many have horrid experiences – At the Police Court today I saw the sworn depositions of an English sergeant (wounded) as to his having watched from a window the Germans putting out the eyes, & cutting off the ears of Belgian & French prisoners before shooting them.

Nor do I think this an extreme, or isolated case.

Two poor naked girls, bleeding to death, reached our (Berkshire) Regiment at Mons, & were wrapped-up by our boys in their coats.

Surely there must be an awful recompense awaiting Germany?

The cutting of hands off wounded, & prisoners, is proved: I have it in a letter from a hospital orderly as to one of his cases.

I don’t recognise the old German character as thus shown – it is as bad as the Turk or Greek.

It is amazing that civilised men should have acted as they have en gros, but to act thus en detail is staggering.’

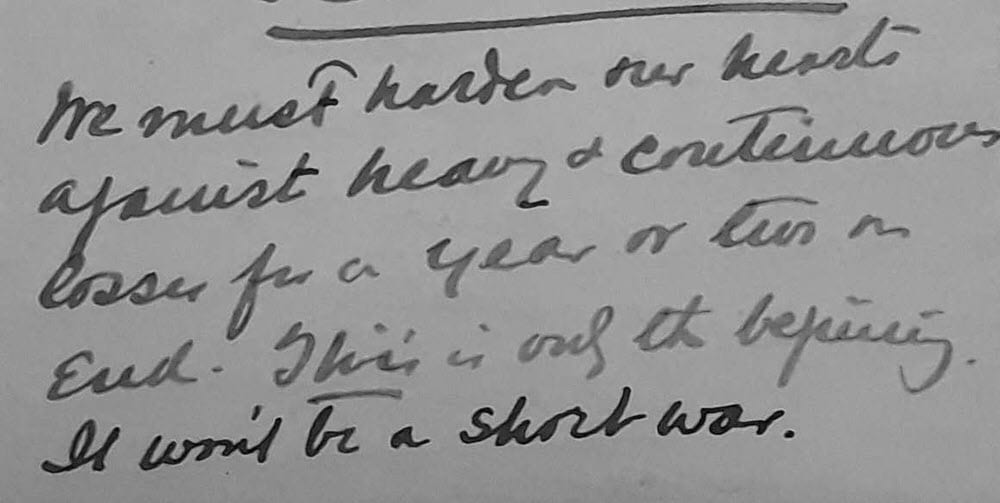

As a postscript, he goes on to make this insightful comment:

‘We must harden our hearts against heavy & continuous losses for a year or two on end. This is only the beginning. It won’t be a short war.’

Henry’s letter of 18 Dec 1916 says:

‘LP [Leighton Park School where Henry’s sons were schooled] has scored three D.S.Os or D.S.Ms, & has 10 O.Ls [Old Leightonians] under the sods in France – May God rest their gallant souls! Amen! – Alas, to Evans’ deep content – one sniveller in Wormwood Scrubs; not for refusing to fight, but for declining to nurse! (O, Lord, how long?)

Evans [Head master at Leighton Park School] says he is equally ‘proud’ of him & – Cadbury!! I’m so glad there’s only him. Nearly 50 young Quakers have already testified for Peace at Any Price with their blood.

Probably 400 are in arms, but you’d never learn this from the pure (but false) columns of the Friend [the Quaker Magazine], where 6 to 9 columns weekly are devoted to the trials of C.O.s, & deaths in action are condensed into 4-5 lines at the foot of the last page.

I tell Evans he must stop his O.L doing these things, downing Zeps, & so forth, or else one will get a V.C. & ruin the school!’

Henry was unapologetic in his support of World War 1, as can be seen above.

Unfortunately, Henry was predeceased by his two sons from his first marriage, Anthony dying in 1919 in Cumberland, after forging a career for himself as H.M Chief Inspector of Schools.

Basil died at the end of January 1917 in Cornwall, not long after Henry’s second letter was written.

In the early 20th century, Henry was Honorary Curator of Zoology (Vertebrates) for Reading Museum for many years and established the nationally important Thames Conservancy Board (TCB) Collection held there.

He continued to travel widely into his eighties, primarily following his interests in zoology and ornithology.

Henry’s interest in Ornithology began during his schooling at Bootham School.

He was a member of the British Ornithologists Union from 1895. In his latter years he continued to regularly attend British Ornithologists Council meetings (British Birds vol. XXXV):

‘he rarely intervened in discussion, but when he did so the vigour and liveliness of his mind were manifest…

He was also a great raconteur and to the end, even when he was bedridden, he would regale visitors with lively stories of his adventures among the birds and in other fields too: certainly his tales lost nothing in the telling.’

Henry died on 10 November 1941 leaving his substantial estate (£27436 11s 9d – equivalent to over £1,000,000 today) to his three surviving children.