This phrase was often used to shame men [who didn’t fight] in the Great War, but what of the women and children in those times?

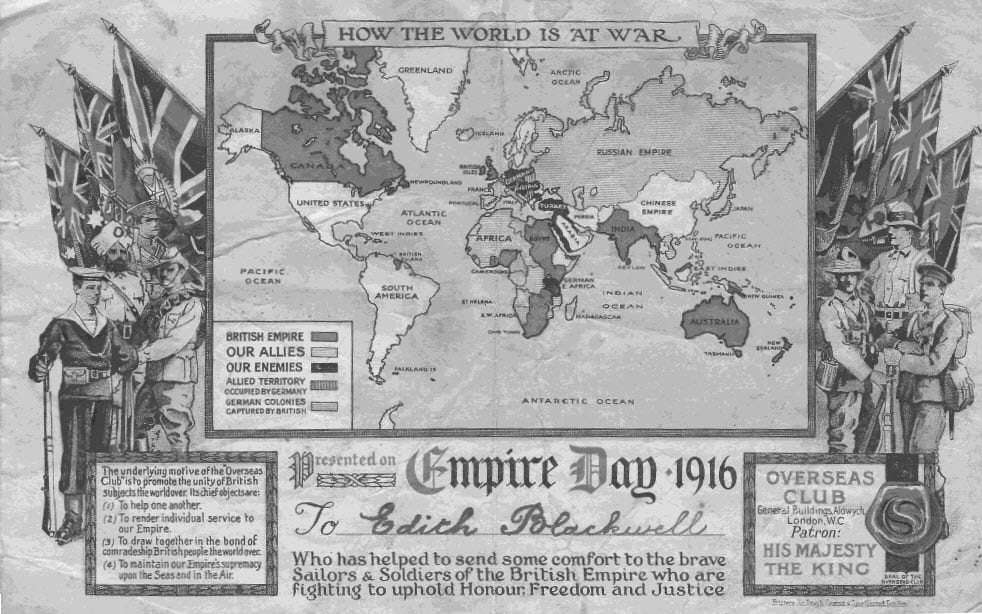

I have already researched the exploits of my Berkshire male ancestors in the Great War (BFH vol. 39 December 2015) but when I was recently handed a certificate given to a young girl in 1916, this set me thinking about what children did to help the war effort in those times.

Edith Blackwell was born in East Woodhay in 1907 to Arthur and Alice Blackwell. She went to Woodhay School, along with her siblings Harry two years younger and Alfred two years her senior.

In 1916, at the height of the Great War and at the age of eight, she was given two certificates one on Empire Day May 24th, the other at Christmas of that year. The [coloured] certificate shows the British Empire in the traditional pink.

Empire Day was first recorded as a notable date in Britain on 24th May 1902, the year after Queen Victoria’s death, commemorating her birthday in 1819 and celebrating the glory of the British Empire. However, although celebrations occurred on that day over the ensuing years, especially across the other Empire nations, the first officially recognised Empire Day in Great Britain was in 1916. After a vigorous debate in parliament as to whether celebrating Empire Day was celebrating militarism or Britishness it was agreed that on this day the Union Jack could be paraded in public.

The Overseas Club awarded these certificates to children who provided tobacco and other comforts in gift boxes to the troops by fundraising. Those who raised the most were given certificates. Possibly Edith and her friends held a “flag day” where children would sell little flags or badges that people could pin to their coats. Flag days were used to raise money for all kinds of wartime projects. This raised money for funding the war effort, for example to build warships, or to help wounded soldiers. There was even a Blue Cross fund to help horses hurt in battle.

The Overseas Club, a charity which organised fundraising, and distributed the certificates to schoolchildren, had been formed in 1910. Upon inauguration its stated motive was to promote the unity of British subjects the world over.

Its chief objectives were:

“(1) To help one another

(2) To render individual service to our Empire

(3) To draw together in the bond of comradeship British people the world over

(4) To maintain our Empire’s supremacy upon the seas.”

Later “and in the air” was added to the 4th line.

In 1915, the charity sent out an appeal to schoolchildren, asking them to raise money so that gift boxes could be purchased and sent to servicemen. Sir Edward Ward, who was in charge of the Overseas Club, wrote to children, asking them to imagine ‘how unhappy [the soldiers] must be…when they have to stand hour after hour, in the trenches, often deep in water, with shells bursting all around.’

Children also collected other things that would be useful for the war effort, such as blankets, books and magazines. These were sent to the soldiers at the front.

Between 1914 and 1918, everyone was expected to ‘do their bit’ to help with war work. Many British children were very keen to lend a hand. They wanted to support their fathers and older brothers who were away fighting at the Front.

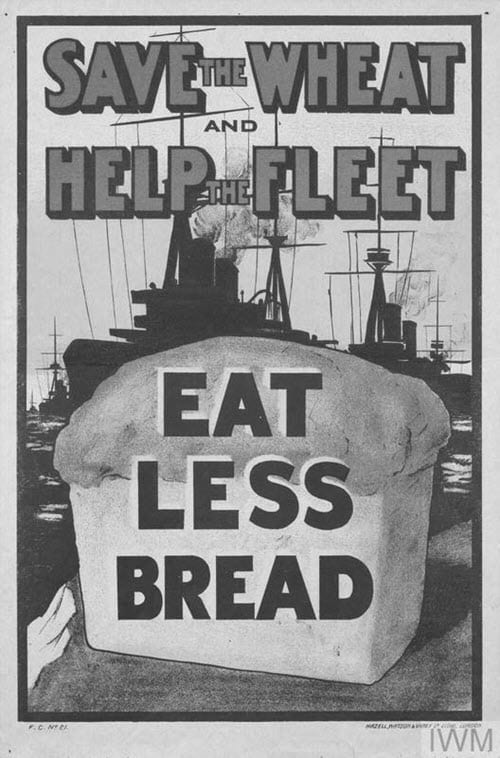

Children did many jobs. Around the home they would look after younger brothers and sisters. They helped with housework, carrying water and chopping firewood. They also joined long queues for food in the shops. Food was scarce because German U-Boats were sinking the ships bringing supplies to Britain. ‘Growing your own’ became very important. Children helped dig and weed vegetable patches and worked in the fields at harvest time.

Conkers were used to manufacture explosives during the Great War. In 1917 children were encouraged to collect conkers and they could earn seven shillings and sixpence (37.5p) for a hundredweight.

Many types of war work were done in schools. The girls were involved in domestic clubs; knitting “comforts” – scarves, socks, balaclava helmets, etc – to send to the troops while some near military camps undertook the mending of uniforms. Others collected jam, chocolate, books and other “comforts” to be sent.

Children also collected scrap metal and other essential materials that could be recycled or used for the war effort.

Children (as well as adults) were also encouraged to eat less with posters such as the one above. Interestingly, rationing was not introduced until 1918 after years of long queues at shops. Meat was limited to two pounds weight per week and sugar and fats to half a pound. Rationing continued after the war and butter was still on ration until 1920. Since Edith and her family lived in the country they may have suffered less from rationing than children in the towns.

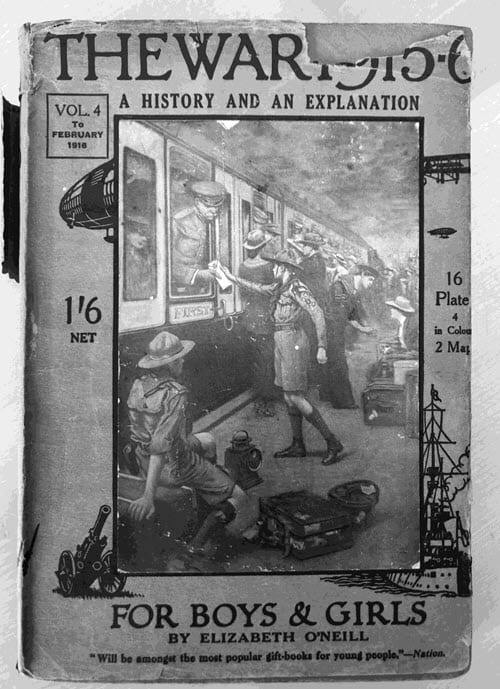

Contemporaneous books about the Great War were written for children by Elizabeth O’Neill e.g. The War 1915-1916 A History for Boys and Girls.

This book, part of a series of 5 volumes, was published in 1916 and gave an upbeat if rather dull reading account of British success.

Edith Blackwell died aged 74 in 1982 and lived her entire life in the Woodhay area. I am grateful to her family for permitting me to tell her Great War story.